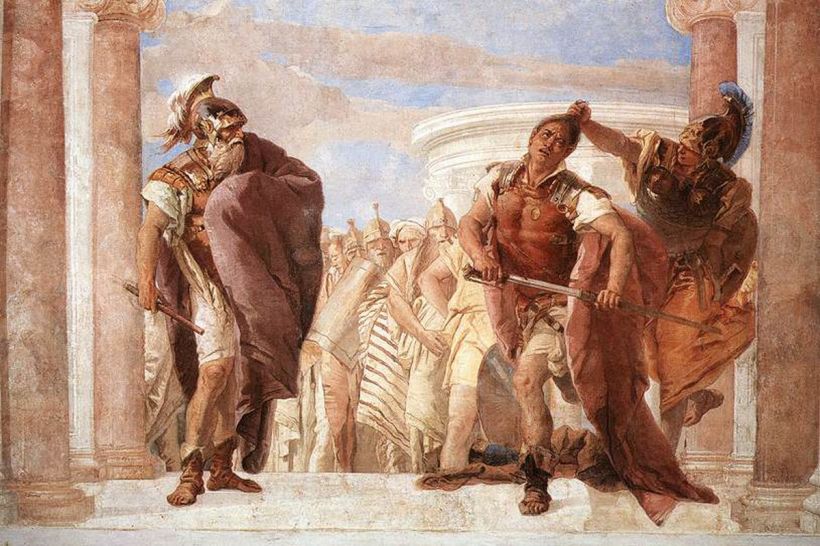

Let all sleep, while to my shame I seeThe imminent death of twenty thousand men Fortinbras is about as minor a character as can be in Shakespeare's Hamlet (1599? 1601?). He is mentioned offhandedly a few times, such as Horatio's re-telling of Hamlet's father killing Fortinbras' father in a duel in Act 1.1, or Claudius [...]

Pascal’s Mugging

I was thinking about dumb logic things today. So, one dumb thing is Roko's Basilisk. It's the dumb rationality obsessed nerd thing where the odds of us being in a computer simulation are less good than us being in reality, so we should give money to a loser who promises to build AI god. The [...]

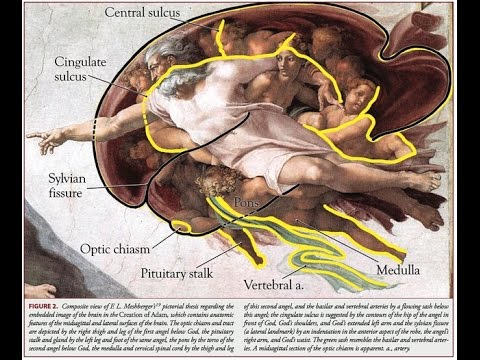

God

A simple proposition: God is Omnipotent. Consider this word: Omni-Potent. Omni, meaning all or of all things. Potent, meaning having great power, influence, or effect. This is not simply "very powerful" or "extremely powerful". This is all powerful. Unlimited. Unbounded. Possessing absolute agency. Non-dependent. Any being which is not omnipotent is not worthy of being [...]

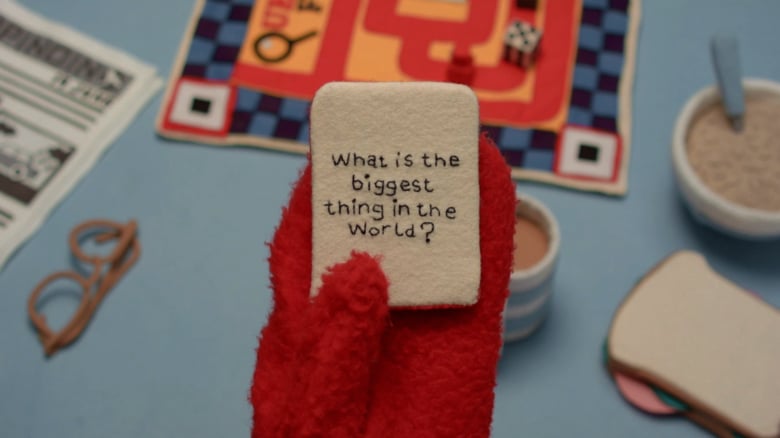

“If only there was a way to learn more about the world…” — Don’t Hug Me I’m Scared

When I was a small child, I was deathly afraid of the Hamburgler. For some reason, that striped, masked, bizarre fellow just disturbed my child self. I can't place exactly why. I had other fears, of course. Certain clowns, moths, the dark, being alone and lost... all pretty common things. Like most children of my [...]

They Can’t Have Disappeared. No Ship That Small Has a Cloaking Device!

The small ship is being pursued from the rebel base, and has emerged from the asteroid field. The larger ship is pursuing it. The small ship, in defiance of all known tactics, suddenly turns and engages the large ship, charging directly at the bridge, flying within feet of the viewing window and causing the bridge [...]

More Than Meets The Eye (Part 1 of X)

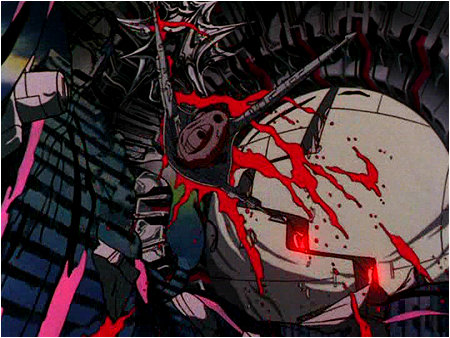

For a certain generation, The Transformers: The Movie (1986) is a traumatic and horrible experience that defined childhood forever. Consider the opening: https://youtu.be/4lo7JPLJUUU We are in space. An eerie, haunting theme plays as, from between two suns, a distant object approaches. It grows closer, and we see it is a large grey sphere, surrounded by spikes, and [...]

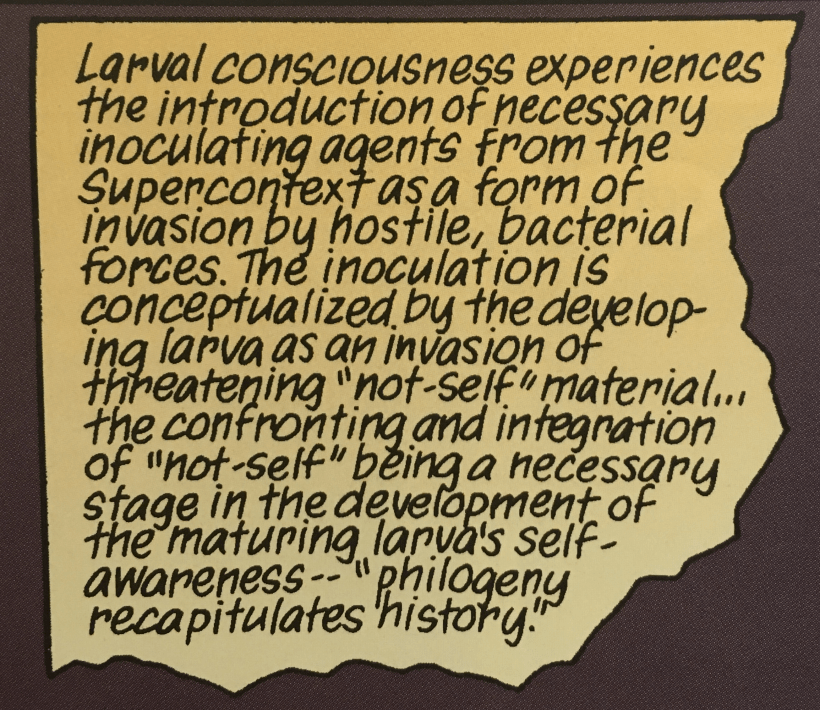

The Invisibles Isn’t Very Good

(This one has been in the queue for a while, and I figure I should get this out before the TV show starts up and everyone starts in with their retrospectives.) Just finished The Invisibles in its nice fat trade paperback editions, and, well, perhaps you had to be there. I mean, I'm reading this comic out [...]

Homer, Robot vs Manual

Homer, The Iliad, translated by Robert Fagles Lines 1-10 Rage-Goddess, sing the rage of Peleus' son Achilles, murderous, doomed, that cost the Achaeans countless losses, hurling down to the House of Death so many sturdy souls, great fighters' souls, but made their bodies carrion, feasts for the dogs and birds, and the will of Zeus [...]

American Evangelion

Everyone who couldn't afford the VHS tapes or DVDs eventually got the chance to watch NGE on Adult Swim, where it was presented in a more or less unedited format, and now a days, it is available to anyone with an internet connection and Google. But back in the late 90's, anime was much harder to [...]